Pockets of Belief

Unlike other species, humans were not born with ingrained social orders. Every social system and network that exists today was created by our shared imagination. Myths are not limited to epic tales of Greek heroes thousands of years ago; they inform our everyday desires and shape our reality. The Chicago Boys believe in free market capitalism. Catholics believe that Jesus was the son of God. Dawn believes it will clean your dishes and your oil-laden seabirds better than other soap brands. "Pockets of Belief" calls into question the mythologies we interact with on a daily basis. What stories do we choose to believe? Can we write our own?

-Anna Reidister

Curated by Randy Aguilar, Anna Reidister, Carlene MacGoldrick, Isola Murry, Hannah Rus

tFeaturing

Patrick Brennan | instagram | website

Jon Ericksen | instagram

Jon Feng | website

Andrew Tarantino Harrington | instagram

Alex Lewis | instagram

Janella Mele | instagram | website

Denver Nuckolls | instagram | website

Anna Reidister | instagram | website

By Sword We Seek Peace

Digital objects

Anna Reidister

I grew up under the dim fluorescent lighting and styrofoam-asbestos drop ceilings that is a Massachusetts public school, where each November little Anna was fed myth after myth of joyous and peaceful Thanksgiving celebrations. I remember the state flag flying proudly in front of the building, right across from the McDonalds which closed down due to a salmonella outbreak. It wasn't until recently that I took a closer look at the imagery on that flag. Adopted in 1780, it depicts a Native American holding a bow and arrow pointed downwards (signifying peace), a five pointed star, an Englishman’s arm brandishing a sword above the native man, and a blue ribbon bearing a Latin motto which loosely translates to “By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty.” This reappropriated seal brings that white supremacist imagery to the forefront, with a full-bodied Miles Standish poised to strike.

self-fulfilling, 2021

oil on canvas

28 x 22 in

Jon Feng

oil on canvas

28 x 22 in

Jon Feng

footsie, 2022

acrylic, modeling paste, and oil on canvas

28 x 22 in

Jon Feng

acrylic, modeling paste, and oil on canvas

28 x 22 in

Jon Feng

These works grapple with how my beliefs about a situation can shape its outcome. The situation here relates to dating. In self-fulfilling, the person contemplates the absence of the one lying next to them. In footsie, two people are flirting, and one is having a much rougher time; this illustrates a fatalistic attitude towards deep connections.

Talking to Ghosts, 2022

Window Installation Accumulation no.1

Janella Mele

A self-reflexivity on the Funny Farm.

Dispelling Hallucinations, 2022

Sumi Ink on Canson and Rug

7 x 30 in

Janella Mele

An Expressionist tracking of medication changes.

The Hurdy-Gurdy Man

And can you hear the Hurdy-Gurdy play?

An old man’s singing on the road to town,

Where people lock their doors, and hide, and say:

“Just let him pass, don’t worry,” while they frown.

He sits down by the well: “Fortune my foe,”

He starts alone, “why dost thou frown on me ...”

Long months he sings: through harvests, roaring snow,

And muddy springs; neglected crops grow free,

And cattle roam; strong keeps through disrepair

Collapse. Old, rich, young, peasants, slaves ...

All mask their faces, shunning even air,

And see in one another walking graves.

The song is done. He smiles, looks around,

And wanders towards new worlds without a sound.

Andrew Tarantino Harrington

The Hurdy-Gurdy Man Artist Statement

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, while I was largely isolated from friends, family, and coworkers, I coped with a sudden sense of world-changing anxiety by turning to my poetry. This particular piece surfaced out of an impulse to draw comparisons between COVID-19 and the bubonic plague. I remembered having once heard about a medieval myth that if an old man playing a hurdy-gurdy (a fiddle-like instrument that replaces bowing with a mechanical motion) came to town, it was

an omen that plague and disaster would follow. Several frantic Google searches trying to confirm that such a myth had ever existed yielded only countless pages about Donovan’s 1968 single Hurdy-Gurdy Man, which, although it’s an enjoyable song, is at best, in a desperately stretched argument, only tangentially relatable to the myth.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, while I was largely isolated from friends, family, and coworkers, I coped with a sudden sense of world-changing anxiety by turning to my poetry. This particular piece surfaced out of an impulse to draw comparisons between COVID-19 and the bubonic plague. I remembered having once heard about a medieval myth that if an old man playing a hurdy-gurdy (a fiddle-like instrument that replaces bowing with a mechanical motion) came to town, it was

an omen that plague and disaster would follow. Several frantic Google searches trying to confirm that such a myth had ever existed yielded only countless pages about Donovan’s 1968 single Hurdy-Gurdy Man, which, although it’s an enjoyable song, is at best, in a desperately stretched argument, only tangentially relatable to the myth.

Ghost Lights

Warm ghost lights never reach where you should look:

Dark wings, vast flies, deep pits beneath the stage,

Cold seats not sold in distant rows, raw rage,

A bloody prop-sword in a hidden nook.

You’d never think to look downstairs, beside

The men’s room, in the coat-check ... on this wall,

A sealed brick archway seems to tell it all:

Here was a tunnel once where someone died.

Look lower than the noisy street: you’ll find

A grand decaying little jewel ... now grave

Of haunting music only time could save,

But when it lived ... the only of its kind.

That portrait leering from the lobby stairs:

He wanders nightly after every show.

Say: “Goodnight Henry,” and he’ll let you go;

But you’ll still feel his ghastly grasp and glares.

There’s older things lost singing out of sight

In murky corners missed by warm ghost lights.

Andrew Tarantino Harrington

Ghost Lights artist statement

As a MA native and long-time resident of Greater Boston, my world has been shaped by the awareness that Boston is a city built as much with myth as it is with brick and cobblestone. Boston myths range from nationally adopted myths (various everently repeated versions of the Boston Tea Party, the revalence in film and television of the immediately recognizable but totally irreplicable Boston accent, and the widely proliferated stereotype that all Bostonians are Irish and related to one another) to the more local and unique myths that “Only a real Bostonian,” might now (the tragic fate of Charlie on the MTA, the pervasive smell of molasses on Hanover St. more than a century after the Great Molasses Flood, a curse placed on the Boston Red Sox after they traded their star player, the ghost of a British Red Coat patrolling the Boylston St. Green Line station ... to name only a few). What seems to lend credibility to many of Boston’s myths is the fact that they are often tied to tangible properties and recognizable landmarks, and so have a physical home that can be visited, and where they can be in some small way experienced

This particular piece came out of my experiences working as part of Boston’s theatre community, an industry saturated with old, historic theatre buildings, many of which carry their own stories and traditions surrounding hauntings and myths. Beneath the Cutler Majestic Theatre, for example, a foreboding sealed archway is the only remaining evidence of an abandoned secret tunnel, which allegedly once connected the theatre’s basement to the nearest subway stop. At the Huntington Avenue Theatre, a grim portrait of an actor playing the title role in Shakespeare’s infamously cursed Scottish Tragedy overlooks the main lobby; according to legend, that actor’s spirit can be seen after dark on the balcony, and staff attest that if you wish his portrait “Goodnight,” before leaving, you’ll prevent his spirit from walking that night. Deep below the Steinert&Sons piano seller on Boylston St. is the once famous but now abandoned underground theatre, Steinert Hall; perhaps because it remains largely unseen and inaccessible to the general public, Steinert Hall has become shrouded in mythic rhetoric, and has achieved an almost legendary status in the psyche of Boston’s theatre world.

As a MA native and long-time resident of Greater Boston, my world has been shaped by the awareness that Boston is a city built as much with myth as it is with brick and cobblestone. Boston myths range from nationally adopted myths (various everently repeated versions of the Boston Tea Party, the revalence in film and television of the immediately recognizable but totally irreplicable Boston accent, and the widely proliferated stereotype that all Bostonians are Irish and related to one another) to the more local and unique myths that “Only a real Bostonian,” might now (the tragic fate of Charlie on the MTA, the pervasive smell of molasses on Hanover St. more than a century after the Great Molasses Flood, a curse placed on the Boston Red Sox after they traded their star player, the ghost of a British Red Coat patrolling the Boylston St. Green Line station ... to name only a few). What seems to lend credibility to many of Boston’s myths is the fact that they are often tied to tangible properties and recognizable landmarks, and so have a physical home that can be visited, and where they can be in some small way experienced

This particular piece came out of my experiences working as part of Boston’s theatre community, an industry saturated with old, historic theatre buildings, many of which carry their own stories and traditions surrounding hauntings and myths. Beneath the Cutler Majestic Theatre, for example, a foreboding sealed archway is the only remaining evidence of an abandoned secret tunnel, which allegedly once connected the theatre’s basement to the nearest subway stop. At the Huntington Avenue Theatre, a grim portrait of an actor playing the title role in Shakespeare’s infamously cursed Scottish Tragedy overlooks the main lobby; according to legend, that actor’s spirit can be seen after dark on the balcony, and staff attest that if you wish his portrait “Goodnight,” before leaving, you’ll prevent his spirit from walking that night. Deep below the Steinert&Sons piano seller on Boylston St. is the once famous but now abandoned underground theatre, Steinert Hall; perhaps because it remains largely unseen and inaccessible to the general public, Steinert Hall has become shrouded in mythic rhetoric, and has achieved an almost legendary status in the psyche of Boston’s theatre world.

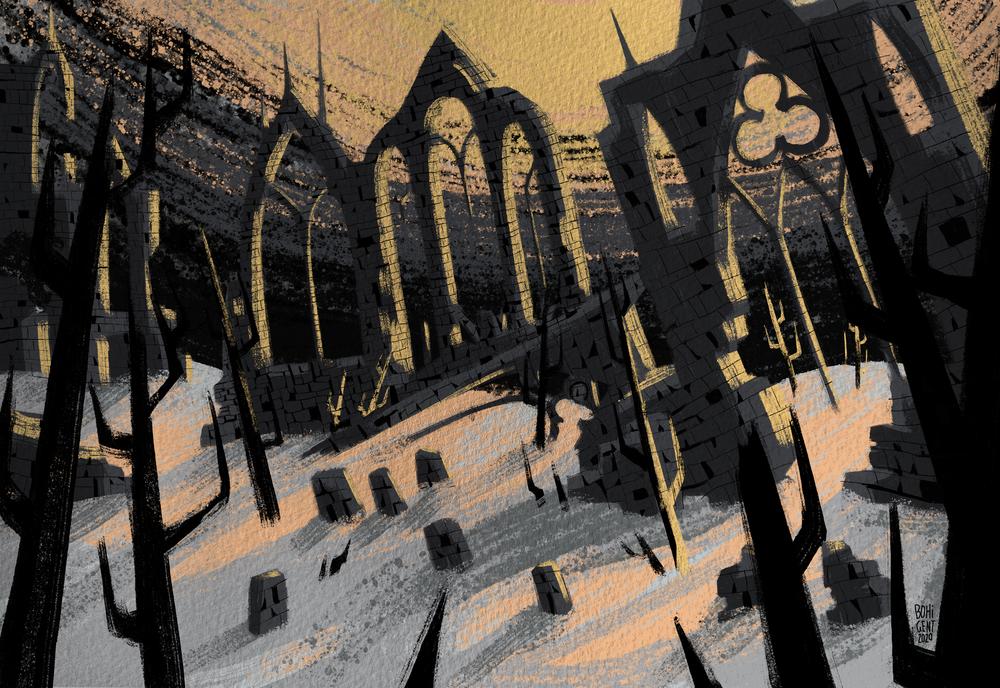

Ruins HH, 2020

Digital

16 x 11 in

Alex Lewis

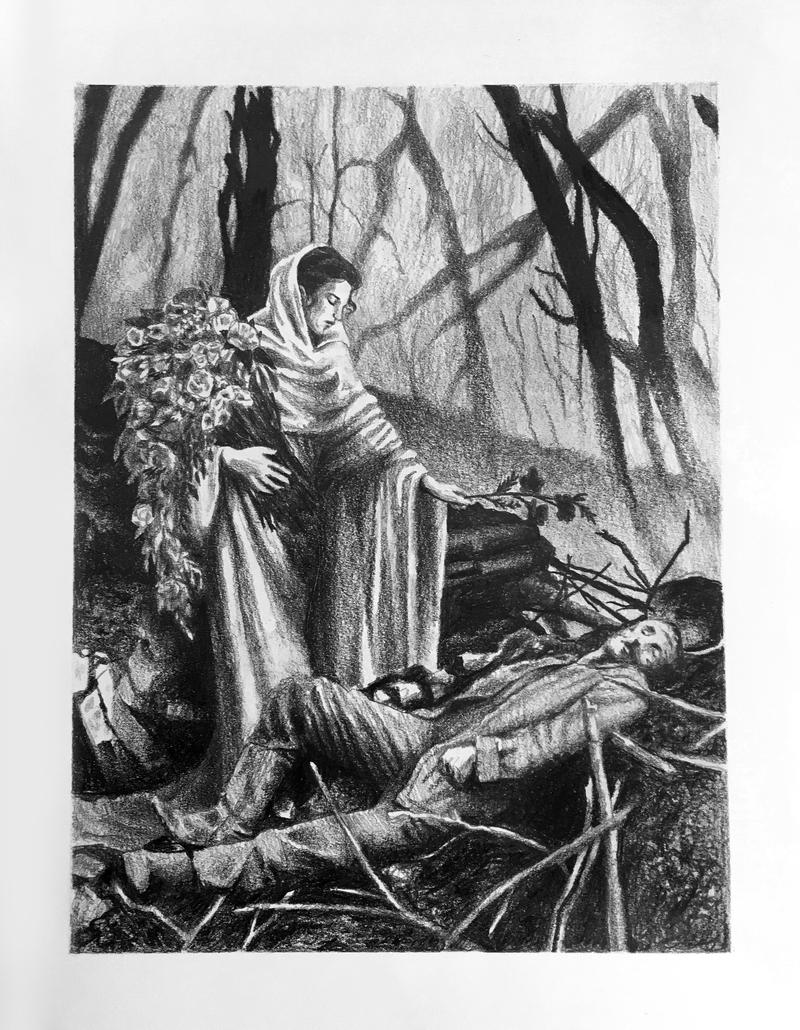

Queen of the Woods, 2021

Graphite on paper

10 x 12.5 in

Alex Lewis

At the central body of my practice is an on-going existential crisis, one that I explore through reflecting on the human condition, with primary emphasis on identity, death, and nature. The prevalence of nature’s impact on the human condition is a constant throughout the work. It is a swan song, a backdrop of repetition, with a notion of homecoming through points of departure or devouring. Traditional mediums are pushed in untraditional ways, while the digital medium is a playing field for experimentation in exploring the bounds of shape language. Works like Dangerous Drinking Water (2021) and Fresh Water (2021) use abandoned objects as a conversation for vulnerable and estranged populations, while pieces like Queen of the Woods (2021)and Ruins HH (2020) examine the constructs and vulnerabilities of mythos. In these works, viewers are invited to consider what it means to be human and how we justify the choices that we make.

Saint Anthony (Pocket Edition), 2017

Oil on Wood Block

2 x 3 in

Jon Ericksen

Concrete, Steel, Earthwork

20 ft x 20 ft x 7 ft

Patrick Brennan

One dream work I always wished to create was a monument to symbolically tell the story of the past, present, and future of the human race through the life of one person. The design work for this sculpture began late in the summer of 2019 and continued until the early spring of 2020. I began construction after the design work was completed, and after nearly a year’s worth of work, the finished statue was unveiled in July 2020.

The first concept piece was constructed in the Massachusetts College of Art and Design courtyard in the winter of 2019.

The second, larger version was constructed in Maynard, Massachusetts in the summer of 2020.

The central monolith is approximately 7 feet tall and made of reinforced concrete.

The three elements of the monument symbolize the three most important things that separate humans from animals. The monolith represents the creation of tools, the torch represents the mastery of fire, and the reliefs represent storytelling.

With 16 relief sculptures, the story of humankind is told symbolically through the life of one person, starting with birth and ending after death with legacy.

The Monument to Humankind (detail)

The first relief is about birth and the genesis of humankind. The idea of birth is reinforced through the symbols of the fruit-bearing tree and the vessel carrying passengers. The snake with the head of a skull and the body sunken under the water are allegories for the death that awaits us from the moment we are born and for the countless dead that allowed for our lives to exist.

The second relief is about play, the innocence of children, and their transition to adulthood through the loss of innocence. The dogs symbolize play and innocence, for unlike children, they never grow out of their eternal innocence. The transition from innocence to adulthood is symbolized by the fruit of the tree and the serpent, representing the apple of knowledge and temptation.

The third relief is about education and the teaching of youth. The owl of wisdom on the head of the child on the left side and the scroll opened by the child and the young man beside him symbolize the passing of knowledge. This piece also portrays the snake-headed teacher as the giver of knowledge, sitting in front of the tree of knowledge. The child holding the torch of knowledge on the bottom right is a symbol for the enlightenment brought about by education.

The fourth relief is about the travel and adventure of young adults when they leave their parents. It shows the perils of failure and potential for success: the snake leads the road to failure while the bird woman leads them to their destination, guided by the distant star. The path of their life is winding and has many setbacks, but they must try again when they fall astray.

The fifth relief is about the first attempt of a young adult to make a life for themselves after they adventure forth into the world. The struggles of making one's own livelihood and becoming fully independent are shown through the fishermen traveling out to the ocean and catching fish with a net and with a rod. The sea, as with all of nature, is unforgiving. Even though their catch seems to be bountiful, large waves summoned by the lady of the sea grow in the distance and could eventually capsize the boat and drown them.

The sixth relief is about the second attempt of a young adult to become self-sufficient. Unlike the first attempt, they ask for guidance from people wiser and more experienced to assist in their struggle, shown by the old man guiding the young man how to hunt deer with a bow and arrow. This piece symbolizes the importance of respecting the wisdom and experience of one's elders, despite their flaws. The flaw of this mentor is shown by the lion pouncing at his back, for no amount of experience can fully prepare one for the harshness of nature, symbolized by the flutist calling the beast to attack the hunters.

The seventh relief is about the first time a young person succeeds in finding their own path and creatively addresses the challenges the world presents them with. This is symbolized by the men working in a team to cut wood and prepare it for a fire, all parts of one group organized to achieve a goal. As the fire is created, a bird rises from it, symbolizing the birth of a new way of life.

The eighth relief is about a time of joy and plenty. This is symbolized by a great feast hosted by a fat and happy man holding a cornucopia and crowned with a torch on his head. Amongst the guests for this feast are the lady of the ocean, the bird born of the fire, and the lady of the woods. Food and drink are bountiful and so are the spirited conversations between guests.

The ninth relief is about a time of stagnation and helplessness. This time of uncertainty and vulnerability is symbolized by three people who find themselves trapped in a frozen wasteland on a cold, dark winter's night. With the assistance of the great winter giant and his large sledge, they will be transported to a more hospitable land. The giant is a symbol for luck, as no amount of determination and hard work could save them if it wasn't for him as well. The moon in this scene is part of a theme continued in the next three reliefs that will represent the transformation of marriage.

The tenth relief is about sex and fertility. This is symbolized using the sowing of a field with seeds by three young men. The first two throw the seeds across the field and the third throws them high into the air, to be carried by the wind to a young woman in the distance. The sun is shown just as it is rising within this scene and is a continuation of the theme shown by the moon in the previous relief.

The eleventh relief is about planning and care. This is symbolized by the man harvesting crops, the pregnant woman, and the mother bird tending to eggs in her nest. In this scene, the sun is shown at noon, high in the sky.

The twelfth relief is about suffering and persistence. This is symbolized through childbirth, shown by the mother holding two newborn twins and by the mother bird caring for her hatched chicks. In this scene the sun is shown setting as this chapter of life has come to its end and a new period of existence begins.

The thirteenth relief is about responsibility and wisdom. This is symbolized through the raising of two children and by the two fully grown birds perched on the branch of the tree on the left side. This scene depicts a ceremony being held by the father for his sons after reaching adulthood; both are given a necklace of jewels to celebrate this achievement.

The fourteenth relief is about loss and despair, shown through the death of one of the sons. The departure of his consciousness is symbolized through a boat traveling into the sea and also by the absence of one of the birds in the tree. His mother, father, and brother mourn him and the mother is about to place a cloth over his face.

The fifteenth relief is about death, cataclysm, and disaster. This is symbolized through the sun destroying all that it has created and marks the end of humanity. In this scene the father and mother are trying to run away from the blinding sun. The mother reaches her hand back to grab the hand of her last surviving son, but none of them survive the heat in the end. Across the right side of the scene, charred corpses litter the ground and the sad face of the sun is shown in the center of the scene with pity for humankind as they are annihilated.

The sixteenth and final relief is about our legacy and the future after humanity is gone. This is symbolized by the sun lighting the torch for the post-human races that follow us. These robed beings carry offerings for the torch and their heads are adorned with crowns symbolizing sentience. Just as during the birth of humankind, the serpent of death is always waiting for them from the moment they are born.