Field Study of the Leaning Bodies/Traces is an ongoing installation project by artist Yolanda He Yang, developed as part of Behind VA Shadows in collaboration with invited curators. Each participating curator selects a color, realized as a vertical band painted onto the gallery wall. Subtle yet deliberate demarcations at hip and shoulder height interrupt these fields of color, registering echoes of bodily contact. These marks reference the project’s focus: the traces left by Visitor Assistants as they lean against the wall for brief moments of respite during extended gallery shifts.

During each installment of new color, artist invites museum workers to leave their bodies of traces onto the wall with charcoal.

read more about the project here

second color: third color:

![]() ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎![]()

![]() more to come

more to come

first color: Morning Sky Blue

During each installment of new color, artist invites museum workers to leave their bodies of traces onto the wall with charcoal.

read more about the project here

second color: third color:

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

more to come

more to comefirst color: Morning Sky Blue

Installed on 1/16/2026

curate by Tessa Bachi Haas

with the support by

Nicky, Nami, Ayla, Cam, , Lexx, Yin Bin

Nicky, Nami, Ayla, Cam, , Lexx, Yin Bin

“I woke up on the first day of 2026 to a bright, blue sky. January in Boston is synonymous with grey, cloudy skies, maybe some rain or snow, waking up in the dark, and spending most evenings in pitch darkness. Winter is a time for slowness, rest, and coziness; to recuperate and reflect on time past, and to celebrate a year ahead. The first days of January embodied this. A blue sky does wonders for the mind and the soul, and we need everyday wonders more than ever...

Blue is the color of a perfectly new day. In Parsi culture, blue is associated with strength, good fortune, and protection from harm, manifesting in the use of turquoise as an embellishment for the home and jewelry. In the United States, blue workwear like indigo-dyed jumpsuits and denim was the norm because a) the dye was cheap and b) the color hid grease and dirt from manual labor, especially during the 19th century when daily washing was difficult. (Coined in 1924, this is where the term "blue-collar" comes from: the actual color of laborers' clothing).

Blue is both peace and action; rest and labor; stillness and movement; protection of self and others. I hope this particular shade, called "morning sky blue," provides space for visitors to reflect on these values as we enter a new year. “ - Tessa

Tessa Bachi Haas is assistant curator at the ICA, where she has organized and supported over a dozen exhibitions since 2022. Tessa is committed to supporting local arts ecologies and fostering an expansive, global exhibition program.

Her recent projects include Christian Marclay: Doors, the 2025 James and Audrey Foster Prize, and the first museum survey of Derrick Adams. At the ICA, Tessa co-manages the museum’s publications program. She has previously held curatorial positions in Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., and has contributed to many exhibitions and catalogues in these cities. Tessa is a Ph.D Candidate in History of Art at Bryn Mawr College, where she earned her MA in 2019.

time for MAINTENANCE!! form______

Happy 2026 everyone! Our collaborative show with The Curated Fridge is on view now~

Current Show

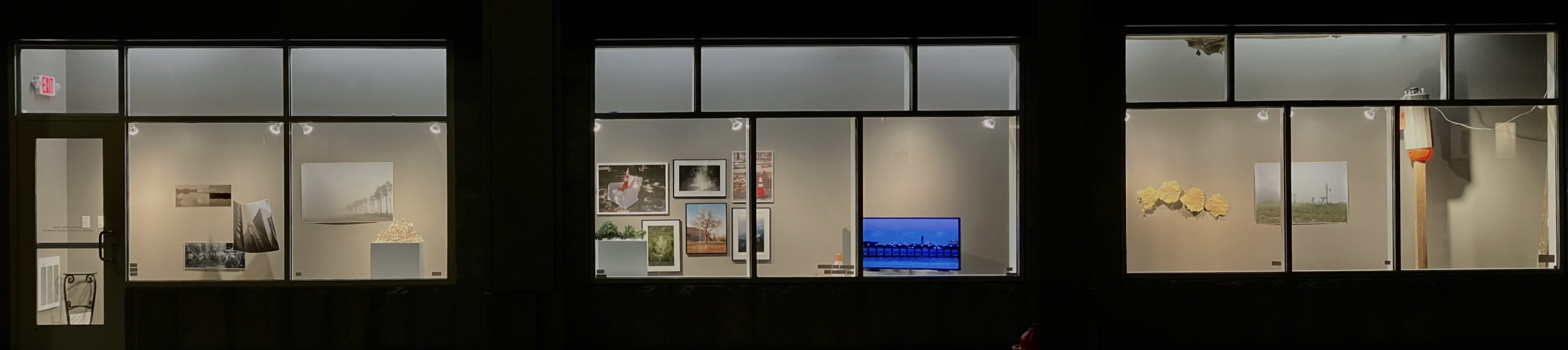

Instant Permenance

Group show guest-curated by Disparate Projects

in collaboration with The Curated Fridge

1/20/2026 - 4/10/2026

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02138

Press

About

Behind VA Shadows is an artists-run DIY public art project founded in December 2021 by a group of Visitor Assistants at the ICA,Boston. Our initiative aims to break down barriers between art and the public, showcasing the creative work of museum workers while extending accessibility beyond institutional walls. By holding the alternative space for the public to engage with the creative identity of museum workers, we advocate for communal care to counter the issues of burnout within art museums and institutions.

We are located at the corner of Mass Ave and 2 Linden St, 02138, Harvard Sq in Cambridge.

Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA. A.

IG

feel free to send all inquires to yolandayanghe@gmail.com

Behind Behind VA Shadows

Yolanda He Yang is a performance, installation artist and community organizer. She is the Founding Director of Behind VA Shadows since 2021.

Yolanda He Yang

she/her

Shelby Feltoon

she/her

Shelby Feltoon is an interdisciplinary artist, educator, and independent curator. Her role at Behind VA Shadows is to lead certain curatorial project and collaborate with and aid guest curators to bring their ideas to life.

Nemo Xu

she/her

Nemo Xu is a writer and an information professional in training. She is the editorial and archival lead of Behind VA Shadows. She works with artists and curators to produce exhibition content regularly and is currently working on building an archives for Behind VA Shadows.

Wenbin Huang

he/him

Wenbin Huang is a graphic designer and photographer. He works on the annual catalog design and photographic documentation of exhibitions and programming at Behind VA Shadows.

Theodora Earthwurms

they/them

Theodora “Earthwurms” Shanahan-Jewett is a multidisciplinary artist whose work centers on personal expression, gender exploration, and identity. Their volunteer work includes Horizons for Homeless Children and Big Brothers Big Sisters. Supporting community project like Behind VA Shadows aligns with their mission to increase access, visibility, and care in creative and educational spaces.

Acknowledgements

This project exists because people showed up, brought ideas, patched the holes during pop-ups, painted floors, and lent their hands, minds, and care in countless ways. Most of those companies are museum workers and museum visitors who care about the unseen labor in the insititutions. They participated the show, joined conversations, read drafts, helped with writing, researched, reached out, asked questions, and thought alongside us as the project shifted and grew. We are deeply grateful to the following people for carrying Behind VA Shadows with us, in all the ways that mattered: Alina Balseiro, Alex Lewis, Amanda Baldwin, Amy L. Green, Andrew Harrington, Anna Reidister, Annie Russell, Ashley Cristiano, BARD, Bell Beecher Pitkin, Ben Hood, Brett Bangell, Cameron Boyce, Carlene McGoldrick, Cj Daly, Claire Pellegrini, Corinne Burkhart, Denver Nuckolls, Eben Haines, Elliot Overmeer, Elias Andrés Taborda, Elisabeth Gerald, Emily Mogavero, Erin Rosengren, Erin She Hogan, Fallon Lavertue, Hannah Rust, Helena Abdelnasser, Kathryn Leaird, Isola Murray, Janella Mele, Jarrod White, Jeannie Dale, Jessie James, Joel Rabadan, Jon Erickson, Jon Feng, Julia Csekö, Juliet Degree, Kayla Scullin, L. Scully, Liam Coughlin, Lindsey Flickinger, Mariana Rey, Mariely Torres, Marjorie Williams, Megha Nair, Miao Suen, Monica Srivastava, Nat Reed, Noelle Stillman, Olivia Hochstadt, Patrick Brennan, Quincey Spagnoletti, Qianyue Chen, Randy Aguilar, Ronan Foley, Ryan Ricci, Sam Ledwidge, Shelby Feltoon, Sophie Tachibana Miller, Sudarshan Sahn, Theodora Earthwurms, Tristan Calvo-Studdy, TylerAnn Mack, Willy Weygint, Working Title Boston, Yueyang Peng (we are still updating the full list of names.)

Past Shows

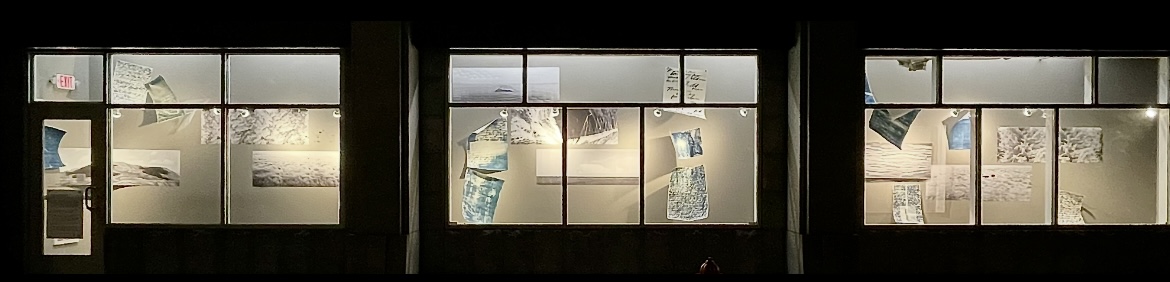

In View

Group show guest-curated by Catherine LeComte Lecce

in collaboration with Photographic Resource Center

December 13, 2025 - January 13, 2026

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02138

Press

Rupture

Group show guest-curated by Maia Erslev

October 15th, 2025 - December 7th, 2025

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02138

Press

On My Way to Work

Group show guest-curated by Nemo Xu

August 15th, 2025 - October 5th, 2025

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02138

Press

Dissection of the Spector

Group show guest-curated by Patrick Brennan

June 17th, 2025 - August 13th, 2025

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02138

Press

Tracing the Familiar

Group show guest-curated by Clarajames Daly

May 20th, 2025 - June 15th, 2025

2 Linden St, Havard Sq, 02134

Press

Incarnated Love

Solo show by Janella Mele

April 26th, 2025 - May 20th, 2025

2 Linden St, Ha

Press

The Student Visitors

a performance and media exhibition featuring students featuring the course

“Advanced Topics in Performance and Media” at Northeastern University

Curated by Kledia Spiro

April 13th, 2025 - Apri 20th, 2025

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

Press

After Flood

Eben Haines solo exhibition

Feburary 16, 2025 - April 10th, 2025

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

Press

Tired Clichés

Isola Murray solo exhibition

December 14, 2024 - Feburary 4, 2025

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

Press

To Grasp the Unattainable

Yueyang Peng solo exhibition

curated by Yolanda He Yang

November 2 - December 2, 2024

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

Press

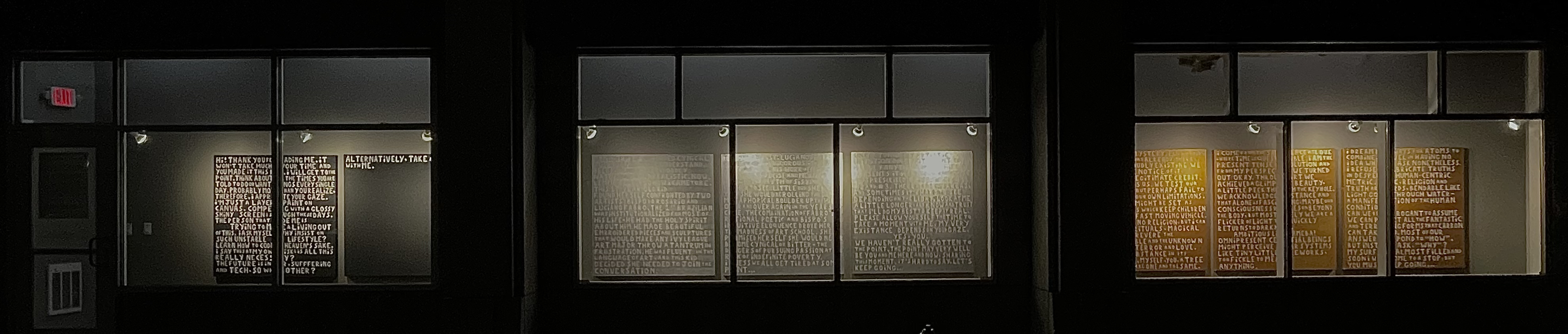

Straight from the Heart - The Rant Series

Julia Csekö’s solo exhibition

selected from Call for Exhibition Proposals

September 14 to October 28, 2024

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

Press

“A Plea To The Nine Muses” Group Show

curated by Jeannie Dale

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

July 14 - August 27th, 2024

Press

“MARGINALIA” Group Show

curated by [Working Title] and Patrick Brennan

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

June 1st - July 4th, 2024

MARGINALIA Digital Mailbox

Press

“Night Studio” Brett Angell Solo Show

curated by Yutong Shi

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

March 18th -May 24th, 2024

Press

“fanfare of clouds opening” Cameron Boyce x Gateway Arts

curated by Yolanda He Yang

2 Linden St, Harvard Sq in Cambridge, MA 02138

December 18th, 2023 to March 1st, 2024

Behind VA Shadows - 25/8 Artspace, Harvard Sq, Cambridge

Group Show “ten minutes worth of sand...”

curated by Shelby Feltoon

October 31 to December 1, 2023

Featuring Artists: Patrick. Brennan, Qianyue Chen, Liam Coughlin, Juliet Degree, Mariana Rey, Noelle Stillman, Jarrod White, Marjorie Williams

Press

Behind VA Shadows - 25/8 Artspace, Harvard Sq, Cambridge

Maria Servellón: “Gl{i}tch,” curated by Yolanda He Yang | September 13 - October 20, 2023

(click to view)

Art Pop : “Chairs & Cares” x Revolutionary Spaces in Old South Meeting House, Boston

curated by Yolanda He Yang | September 24th, 25th, 2023

![]()

Featuring Artists : BARD, Patrick Brennan, Shelby Feltoon, Theodora Earthwurms, Cameron Boyce, Will Weygint, Isola Murray, Ryan Ricci, Liam Coughlin, Kayla Sculli, Helena Abdelnasser, Denver Nuckolls, Working Title - L Scully, k.i.n.d.re.d- Erin Shea Hogancurated by Yolanda He Yang | September 24th, 25th, 2023

Behind VA Shadows - 25/8 Artspace, Harvard Sq, Cambridge

Nat Reed: “Bikes Move Us” curated by Yolanda He Yang | June 19 - September 14 , 2023

Artscope Online | Boston Art Review

Laconia Gallery, Boston

Group Show: “The Landscape of Our Minds” curated by Yolanda He Yang | Feburary 3 - April 16, 2023

Downtown Crossing, Boston

Group Show: “via” curated by Yolanda He Yang | June 1 - June 17, 2022

Online Group Shows

Discipline of Sleep | 1.30.23

(click to view works)

![]()

Unfolding | 11.18.22

(click to view works)

![]()

(un)Veil | 8.20.22

(click to view works)

![]()

Pockets of Belief | 4.8.22

(click to view works)

![]()

Translation - Tessellation | 3.11.22

(click to view works)

(click to view works)

Unfolding | 11.18.22

(click to view works)

(un)Veil | 8.20.22

(click to view works)

Pockets of Belief | 4.8.22

(click to view works)

Translation - Tessellation | 3.11.22

(click to view works)

Raison D'etre | 2.11.22